SELECTED

ISSUE

SELECTED

ISSUE

|

|

Leisure Management - Watching your waste

Hospitality

|

|

| Watching your waste

|

If food wasn’t wasted, there would be enough for everyone. That’s

the message from waste not want not cafés. Kath Hudson reports

|

|

Fifteen million tonnes of food is wasted every year in the UK. On average, consumers waste about one third of the food they buy, which equates to about £30 a week, either because it goes beyond sell by dates, they don’t know what to do with it, or don’t have time to cook. Avoidable household food waste in the UK is associated with 17m tonnes of CO2 emissions a year. The food industry’s obsession with sell by dates and the supermarkets' insistence on perfectly formed vegetables exacerbates the problem, and has sparked a burgeoning trend for waste not, want not cafés. They are popping up all over the UK and the US and projects are afoot in South Africa, France and South America. These cafés operate on the principle of transforming intercepted food – which would otherwise be thrown away by supermarkets and wholesalers – into tasty dishes. Menus change daily, using whatever food is available, so if there’s no sugar for coffee, there’s no sugar for coffee. Customers pay according to what they feel the meal is worth and occasionally offer services instead. The operators agree that they want to be out of business within 15 years, hoping that by then policy changes will have occurred which will make them redundant. The French government has already seen sense and in May announced a law to crack down on food waste to avoid 7.1m tonnes of wasted food a year, at a cost of €20bn. All French supermarkets will be banned from throwing away or destroying unsold food and must instead donate it to charities, or for animal feed. The measures are part of a wider drive to halve the amount of food waste in France by 2025.

|

|

|

Skipchen, Bristol, UK

The idea of people giving a donation tests their connection with money and decision making

“Skipchen is a campaign café. We campaign against food waste and for a change in government policy: too much food is going to waste when people are hungry,” says Catie Jarman, co-founder of Skipchen.

The café opened last year in the Stokes Cross area of Bristol – infamous for its radical politics and opposition to gentrification – and was chosen because of its potential for high footfall.

“The main challenge has been to make the café sustain itself and to get the message across that it’s not just free food, it’s a pay as you feel concept,” says Jarman. “The idea of people giving a donation tests their connection with money and decision making. We see a big range: some people are incredibly generous and see it as a charitable donation, some people are homeless or don’t have any money, a few just want to get something for nothing.”

The food comes from independent shops and restaurants, individuals, wholesale distributors and supermarkets. Everything is donated, they don’t even keep staples in such as spices or herbs, so the dishes vary greatly and they have to be flexible.

“We cook on a big scale, as we average 150 people in three hours,” says Jarman. “We try to cook a meat, vegetarian and vegan dish. The only waste we generate is peelings, bruises and plate scrapings. We tend to sell out every day, but if there is any leftover food, it is donated to Food Banks.”

| |

|

The Skipchen team including Catie Jarman (bottom right) |

| |

|

| This summer, Skipchen took the café on tour with its food rescue ambulance |

| |

| |

|

| This summer, Skipchen took the café on tour with its food rescue ambulance |

| |

| |

|

| Diners pay what they feel they can afford for the food at the Skipchen café in Bristol |

| |

|

|

Blue Hill Restaurant, New York, US

We didn’t want this to be a novelty project. Bottom line, every dish had to be delicious

This family-owned restaurant opened in New York City in 2000, with the aim of showcasing ingredients from the family farm in the Hudson Valley. Earlier this year they decided to shake things up by closing the Blue Hill Restaurant for three weeks and reinventing it as a pop-up called wastED, to highlight the issue of food waste. All food in the restaurant is made from waste.

“We hoped the project would raise consciousness and start a conversation, but we didn’t want to sermonize about food waste,” says co-owner Dan Barber. “The real goal was to celebrate a tradition of cooking that uses creativity and technique to transform lowly, uncoveted ingredients. Hopefully we’re inspiring people to take this back to their own kitchens.”

Barber says it was like opening a new restaurant, as they learned to work with a new vocabulary of ingredients and vendors. Twenty guest chefs were brought in to curate daily specials. “We didn’t want this to be a novelty project. Bottom line, every dish had to be delicious, it had to stand on its own,” says Barber.

“Sourcing ingredients in sufficient quantity was probably our greatest challenge,” he says. “There were several ingredients that we wanted to include on the menu – like broccoli cores and sardine skeletons – that we had to scrap because we just couldn’t find an adequate supply. Ultimately, I think it forced us to get more creative. We had to look more closely at some of the ignored byprodcuts of our food system, like dry-aged beef ends and cascara.”

Architectural design firm, Formlessfinder, which has a track record of reexamining raw and waste materials for architectural purposes, was brought in to imagine the architectural and design equivalent of the waste-food concept. “The design process was informed by many tours of the farm, kitchens and greenhouses to source materials which in one way or another dealt with waste,” says Formlessfinder principal, Garrett Ricciardi.

Tables were made out of mycelium and agricultural waste and the wall covering, which reveals glimpses of the permanent restaurant behind, was made from a translucent agricultural fabric called remay, which is used to cover crops inside the greenhouses and helps prevent waste in the field.

“For the seating, we designed a custom table-top that’s grown from mushroom and corn waste,” says Ricciardi. “It’s a very interesting material and process which gives them an almost edible, food-like quality – and is the first commercial product of its kind.”

The pop-up attracted a new audience of younger, more adventurous eaters who were curious about the concept and excited to try new ingredients, so the team are planning to repeat the concept again next year, although are yet undecided what shape it will take. In the meantime, they are still raising awareness with other projects, including a recent partnership with Shake Shack in Madison Square Park. For one day, the wastED veggie burger, primarily made with beet and carrot pulp left over from a cold-pressed juice facility, was served as a special.

| |

|

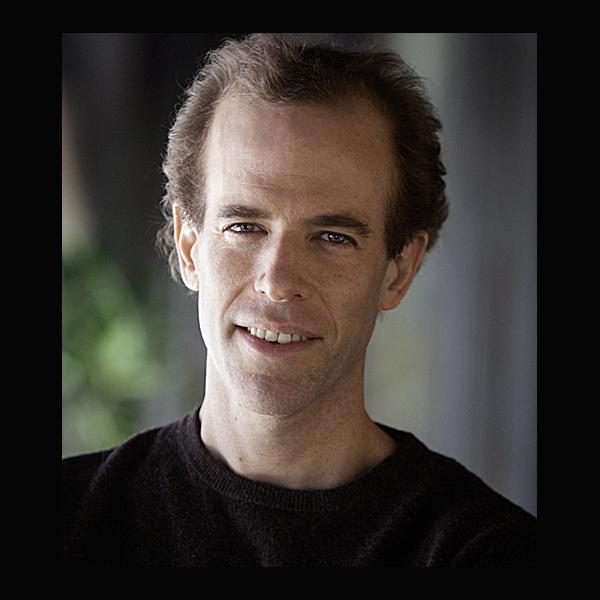

| Photo: Mark Ostow |

Dan Barber |

| |

|

| Pop up restaurant wastED aimed to highlight the issue of food waste |

| |

| |

|

| Dishes on the wastED menu included Dumpster Dive Salad and Dog Food with Unfit Potatoes and Gravy. The dishes were created by guest chefs while the space was designed by Formlessfinder |

| |

| |

|

| Unusual organic materials were used in the decor at wastED |

| |

| |

|

| Unusual organic materials were used in the decor at wastED |

| |

|

|

The aim is to create a consciousness

about the effect of everyday food choices

In May this year, the respected James Beard Foundation named Blue Hill at Stone Barns – the restaurant at Pocantico Hills, north of New York City – as the best in the US. The restaurant has been a champion of the farm-to-table movement since its inception.

Stone Barns promotes sustainable agriculture, local food, and community-supported agriculture.

The Blue Hill business is owned by family proprietors David, Laureen and Dan Barber, who took the best US chef honor in 2009. Blue Hill is the name for their two restaurants, Blue Hill at Stone Barns and Blue Hill Restaurant Greenwich Village in NYC It's also the name of the farm that inspired them.

The Blue Hill at Stone Barns restaurant is within the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture. This is where the Barbers created the philosophical and practical framework for their business and is a working four-season farm and educational centre. The aim is to create a consciousness about the effect of everyday food choices. The centre has recently moved to ticketed admission at weekends to control demand.

There are no menus at Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Instead, guests are offered the multi-taste 'Grazing, Rooting, Pecking' menu featuring the best offerings from the field and market.

The Blue Hill Café – a respite for families and hikers – offers light snacks, farm-fresh lattes, and other locally-grown goodies. Fresh baked goods and vegetable salads prepared in Blue Hill's kitchen are available to eat in the courtyard or to take on a walk around the farm. Blue Hill’s savoury vegetable yogurts are available for sale at the Café.

To find out more about Blue Hill Greenwich Village and its wastED pop-up concept go to bluehillfarm.com

| |

|

| Blue Hill at Stone Barns |

| |

| |

|

| Blue Hill uses locally sourced produce. The business is owned by the Barber family |

| |

|

|

The Real Food Project, Leeds, UK

One of their main concerns is the environmental impact of food waste

The Real Food Project has built up a nine-strong chain of waste food cafés in Leeds with the latest site, City Junction, launched in May. The plan is to close all the restaurants within 15 years.

Some 200 volunteers are involved with this operation, which was started by Adam Smith and Joanna Hewitt. They were appalled by the amount of food wastage they witnessed while working in Australia and decided they wanted to intercept this and feed the world. They returned to their home city of Leeds to start their campaign.

One of their main concerns is the environmental impact of food waste. “When we talk about food waste we only tend to see the end product: an avocado for £1,” says Payam Mohseni, co-director of The Real Food Project. “We’re detached from where food comes from, so what we fail to see is the time and energy which has gone into producing that avocado and the distribution network it has been through. That’s the hidden impact of food waste.”

Mohseni argues the food industry doesn’t help the issue by the practice of use by and sell by dates, which are not relevant to whether or not the food is edible. Also, the industry makes it difficult to buy some food, like onions, in small quantities.

The City Food Project is keen to inspire and help other cafés all over the world and sends its business plan, for free, to those who want to set up similar operations. It receives enquiries from all over the world and is helping similar projects get underway in France and Sourth Africa.

“We run on a pay as you feel basis, which is different from pay what you want, which implies you have to give money,” says Mohseni. “Sometimes people pay in kind. For example an electrician offered to rewire the café instead of pay and a design student made us a poster. One guy, who is out of work, regularly cleans the windows.”

Going forward, they are considering the launch of a teaching kitchen to pass on cooking skills. “Lots of people on low incomes don’t know how to cook and are reliant on ready meals, which will have a long term health impact,” says Mohseni.

| |

|

The team behind the Real Food Project. They use waste food from a variety of sources, including student flats |

| |

|

| The team behind the Real Food Project. They use waste food from a variety of sources, including student flats |

| |

| |

|

| The team behind the Real Food Project. They use waste food from a variety of sources, including student flats |

| |

|

|

| Originally published in Leisure Management 2015 issue 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|