SELECTED

ISSUE

SELECTED

ISSUE

|

|

Leisure Management - Talking Point

Opinion

|

|

| Talking Point

|

While rare, the sudden, unexpected death of an athlete is always a tragedy that sends shockwaves through sport. Tom Walker finds out how the industry is preventing such deaths among elite and grassroots players

Tom Walker, Leisure Media

|

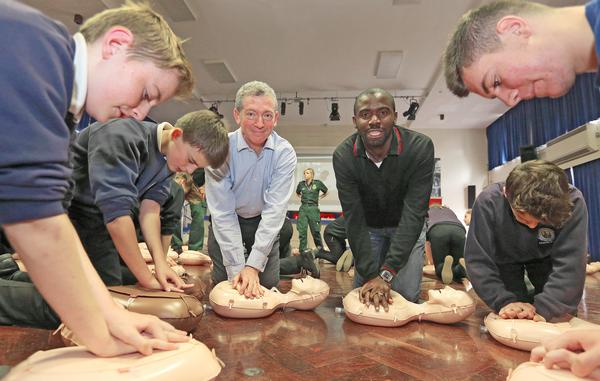

Ex-footballer Fabrice Muamba now raises awareness of sudden cardiac arrest © Matt Alexander/PA Archive/PA Images

Muamba recovered despite his heart stopping for 78 minutes © Joe Giddens/EMPICS Sport

|

|

|

When Manchester City and Cameroon star Marc Vivien Foé collapsed and died during an international match in 2003, it shocked the entire footballing world – and raised awareness of sudden cardiac arrest among athletes. Sadly, since Foé’s demise, football has suffered a number of similar, distressing incidents. Perhaps the most high-profile case in recent years was that of Fabrice Muamba, the Bolton Wanderers and England U-21 midfielder, who suffered a heart-attack during a televised FA Cup Quarter Final match in 2012. Fortunately, Muamba recovered – despite his heart having stopped for 78 minutes – but was forced to retire from professional football. He now actively campaigns to raise awareness of sudden cardiac arrest. Many other sports have had their own, similar tragedies. Neil Desai, a promising, 22-year-old world-ranked squash player; Alexei Cherepanov, a “super talented” 19-year-old Russian ice hockey player; Frederiek Nolf, a 21-year-old Belgian cyclist riding with the Topsport team were among the fit, young athletes who succumbed to sudden, unexpected cardiac arrest while playing their sport. Just this year, the deaths of two rugby players in New Zealand – Waitohi prop Bevan Moody and Wellington star Daniel Baldwin – traumatised those who were involved in the country’s national sport. The world also mourned former Newcastle FC player Cheick Tiote when he suffered a fatal heart attack during training with his new team, Beijing Enterprises. It isn’t just elite athletes who are at risk, either. While it may be mistakenly assumed that sudden cardiac arrest results from finely-tuned athletes pushing themselves too hard, or unfit amateurs overexerting themselves, the truth is that people of all fitness levels can carry undetected heart defects. More than a quarter of sudden cardiac events are blamed on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) – a genetic condition caused by a mutation in one or more genes, carried by around one in 500 people. The discovery of a causal link has led to increased screening for the condition, with the most common tests for HCM being electrocardiogram (measuring the electrical activity of the heart), echocardiogram (showing the pumping action of a heart) and an exercise stress test. At elite level, cardiac screening of athletes has now become a focus for sports medicine teams and many sports associations and organisations, including the International Olympic Committee, have issued recommendations regarding screening practices in an effort to prevent – or at least limit the number – of sudden cardiac arrests in athletes. At grassroots level, sports clubs are becoming increasingly aware of the need for defibrillators – a life-saving piece of equipment which, if used in tandem with CPR during heart attacks, can help increase the chances of survival by up to 70 per cent. But is there more we can be doing? To find out, we spoke to experts and people in the field about their experiences.

|

|

|

Conleth Donnelly

Development officer

Sport Northern Ireland

|

|

In July 2016, Sport Northern Ireland launched its Defibrillators for Sport initiative, in partnership with the Department for Communities NI and the Northern Ireland Ambulance Service. Modern AEDs (automated external defibrillators) can make a massive difference when an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) occurs, particularly in the critical period before an ambulance arrives.

While 1,000 AEDs were available outside of hospitals in Northern Ireland before the programme launched, there was no comprehensive record of who had a device, where they were located and who had access.

Recognising the risk of OHCAs in a sport setting, and the role of clubs and centres as community ‘hubs’ for people here, the Defibrillators for Sport initiative invited clubs and community organisations to apply for a free AED device through Sport NI.

The initiative aimed to increase the number of AED devices available in community settings. It also included a mapping exercise conducted in partnership with the NI Ambulance Service to record the location of the allocated devices.

The allocation model ensured devices were evenly distributed across Northern Ireland’s 11 local council areas, and particularly in rurally isolated areas. By the end of the project, 1,094 AEDs will have been distributed. We’re now working with councils and the NI Ambulance Service on developing more robust systems for maintaining AEDs.

"By the end of the project, 1,094 AEDs will have been distributed around Northern Ireland’s local council areas"

|

|

|

Dr Steven Cox

CEO

Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY)

|

|

Every week in the UK, around 12 apparently fit and healthy young people aged 35 and under, die suddenly from a previously undiagnosed heart condition. Eighty per cent of these young sudden cardiac deaths (YSCD) will occur with no prior symptoms – which is why CRY believes screening is so vitally important.

Screening won’t identify all young people at risk, but in Italy, where screening is mandatory for young people engaged in organised sport, the incidence of young sudden cardiac death has been reduced by 90 per cent. Sport does not cause sudden cardiac death but it can significantly increase risk if a young person has an underlying condition.

CRY now tests more than 23,000 young people, aged 14 to 35, every year through its pioneering screening programme, which is overseen by world leading cardiologist professor, Sanjay Sharma.

Many of those tested will be young people playing at grassroots level as well as those not involved in regular sport. To prevent YSCD, facility operators should take into account some key points.

Be aware of cardiac signs and symptoms – if a person passes out or feels chest pain during exercise, they should contact CRY. Operators can make people aware they can have free cardiac screening if aged between 14 and 35 – book an appointment at www.testmyheart.org.uk.

If all young people were checked, and everyone learned CPR, hundreds of lives could be saved.

"CRY now tests more than 23,000 young people, aged 14 to 35, every year through its pioneering screening"

| |

|

| © shutterstock/ Kittisak Jirasittichai |

If a young person passes out or feels chest pain during exercise, they should get screened by CRY |

|

|

|

Dr Mike Knapton

Associate medical director,

British Heart Foundation

|

|

The two most important measures in helping to prevent sudden cardiac deaths are prompt cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation, along with early identification of people who have these, often hidden, conditions.

CPR is a crucial, lifesaving skill. Sports clubs and facility operators should provide CPR training for their players and staff, to ensure they have trained first aiders at all training sessions and matches, and access to defibrillators.

In the UK around 600,000 people have a faulty gene that causes an inherited heart condition, which can significantly increase your risk of a sudden cardiac death. Every week in the UK 12 people aged 35 and under die of an undiagnosed heart condition.

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) is funding research to identify the faulty genes that cause these conditions and understand how they work. We’re applying these research findings to improve survival rates through early identification and treatment.

This is where genetic cascade testing comes in. The UK is ahead of the game in this, thanks to BHF investment. Cascade testing is a screening tool that identifies people at risk of a genetic condition by a process of systematic family tracing. So when someone is identified as having an inherited heart condition, their close biological relatives are also tested.

Through the Miles Frost Fund we’re funding specialist genetic nurses to run testing in UK centres, and we also support Heartstart schemes to deliver free CPR training at sports clubs and in communities.

"We’re funding research to identify the faulty genes that cause these conditions and understand how they work"

|

|

|

Christophe Lavialle

Chair

Mini and youth section, Hitchin Rugby Football Club

|

|

Our U-10 coach, a very fit and healthy guy, had a sudden cardiac arrest and collapsed during an evening training session. We had a number of youth teams training at the time, so there were other coaches around – some of whom had trained as first aiders and were able to attend to him. One of the coaches started CPR and another retrieved the defibrillator, which we had acquired about a year earlier through an initiative run by Eastern England Ambulance Service. The coaches continued giving CPR for the full 15 minutes until an ambulance arrived. It was undoubtedly due to these actions that he made a full recovery.

Before this incident, we hadn’t really considered or planned for a cardiac event specifically, but had made big investments in first aid provision as a club.

In total, we spend around 30 per cent of our annual budget on first aid. It’s a lot, but it underlines our commitment to the safety and welfare of our members and the wider community who visit our facility.

The investment enables us to always have at least one paramedic present during all training sessions and games. As we’re quite a successful club at youth level (we have 600 children on our books) we have a lot of games at the same time, spread out across a large area. Having an ambulance present reassures parents and players.

There were some simple lessons we gained from the incident, such as ensuring no-one parks in front of the ambulance access gate.

We’re also committed to training more of our coaches and members in first aid so we can respond to any incident successfully every time.

"Our investment enables us to always have at least one paramedic present during all training sessions and games"

| |

|

| © Lynne Cameron/PA Archive/PA Images |

Hitchin RFC spends 30 per cent of its annual budget on first aid to keep its members safe |

|

|

|

What to do in an emergency – East of England Ambulance Service advice

A cardiac arrest is an emergency. If you witness a cardiac arrest, you can greatly increase the person’s chances of survival by phoning 999 immediately and giving CPR.

CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) means:

• Chest compression (pumping the heart by external cardiac massage), to keep the circulation going until the ambulance arrives

• Rescue breathing (inflating the lungs by using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation).

Remember – even if you haven’t been trained in CPR with rescue breathing, you can still use hands-only CPR. It is possible for a person to survive and recover from a cardiac arrest if they get the right treatment quickly.

Ventricular Fibrillation can sometimes be corrected by giving an electric shock through the chest wall, by using a device called a defibrillator. This can be done in the ambulance or at hospital, or it can be done by a member of the public at the scene of a cardiac arrest if there is a community defibrillator nearby.

Immediate CPR can be used to keep oxygen circulating around the body until a defibrillator can be used and/or until the ambulance arrives. Sporting facilities and other leisure centres can help by ensuring they have community defibrillators installed, and in the event that an athlete collapses and goes into cardiac arrest that they call 999 and follow the instructions of the trained call handler.

| |

|

| © shutterstock/ ms.nen |

Defibrillators can help save lives |

|

|

| Originally published in Sports Management Sep Oct 2017 issue 133

|

|

|

|

|

|